1.0 Introduction

Vegetative state syndrome (VS) is a rare but extremely devastating neurological disorder resulting from severe brain damage. The increasing sophistication of critical neural care has made it possible for people to be kept alive with only the barest of brain function; machines can now take over the control and regulation of basic organic functions. An estimated 13,000-44,000 Americans are currently in a vegetative state. The causes of VS are diverse ranging from traumatic brain damage such as from car accidents to hypoxia from drowning, stroke, heart attack, or drug overdoses. VS is considered a disorder of consciousness insofar as it is assumed to deeply affect conscious awareness. Hence, VS is widely described as “wakefulness without awareness” or “wakeful unawareness” (Jennet & Plum, 1972).

When most laypersons hear about VS they think about so called “persistent vegetative state” which is a term used to describe VS patients 1 month after acute injury. Persistent VS is often confused with permanent VS which is defined by the Multi-Society Task Force as a VS state 3 months after a non-traumatic brain injury and 12 months after traumatic injury. VS is often confused with brain death, which is the complete and irreversible cessation of neurological function. VS is also distinct from being in a coma, a term that comes from the ancient Greek term “koma”, meaning “deep sleep” (Fig. 1). Coma is operationally defined in terms of a complete lack of overt response to vigorous stimulation and attempts to arouse the patient. Plum and Posner define the state of coma as being

unarousable, unaware of all elements in the environment, with no spontaneous interaction or awareness of the interviewer, so that the interview is difficult or impossible even with maximum prodding (2007, p. 184).

Coma patients are still breathing and their basic physiological systems are still functioning but their eyes never open and they appear to be in a deep sleep marked by a presumed total lack of consciousness. If a patient recovers from a coma at all, they typically begin to recover after a week or two, transitioning through progressive stages starting with vegetative state and ideally moving through a continuum of minimally conscious states to either locked-in syndrome, or a full cognitive recovery.

Fig. 1 From (Posner, 2008).

2.0 Ancient to Modern Conceptions of the Vegetative State

The concept of VS can be indirectly traced by to Ancient Greece and the Hippocratic school of medicine (400-200 BCE), sometimes called the “Coan school” because it was apparently located on the island of Cos in the Aegean Sea. Some scholars believe that the Hippocratic school was an ancient Pythagerean-like cult that had a quasi-religious and mystical set of beliefs and initiation rights. In Ancient Greek medicine one of the terms closest to referring to what is now called the vegetative is the condition called “apoplexy”, referred to stroke or brain hemorrhage, meaning “being struck by violence”. Due to the complete lack of knowledge of how brain damage affected cognitive function, the ancient Greeks lumped many more neurological conditions under the same category than we would do now. Consider the following Hippocratic description of apoplexy

The healthy subject is taken with sudden pain; he immediately loses his speech and rattles his throat. His mouth gapes and if one calls him or stirs im he only groans but understands nothing. He urinates copiously without being aware of it. If ever does not supervene, he succumbs in seven days, but if it does he usually recovers (Clarke, 1963, p. 307)

Besides the Hippocratic writings, the most comprehensive source of Ancient knowledge about apoplexy comes from the works of Galen written between 200-150 BCE.Although Galen’s writings on apoplexy were fragmented and scattered through his corpus, his writings on the subject constitute the first medical taxonomy of the condition. According to Galen, “Apoplexy [is] a palsy of the whole body, accompanied by impairment of its leading functions” (Quoted in Karenberg, 1994, p. 87).

Since Galen, little progress in diagnosing, understanding or treating apoplexy was made in between ancient Greece and the the beginning of the Enlightenment and the birth of modern, mechanistic approaches to medicine such as William Harvey’s hydraulic model of the circulatory system. Much of this lack of progress can be chalked up to the collapse of the Roman empire, the rise of the institutions of the Church and numerous other complex social, economic, and political factors. The scholastic and highly conservative nature of medicine essentially kept the Hippocratic conception of apoplexy intact all the way up through the 17th century. For example, when we read 17 century doctor Thomas Willis’ description of apoplexy, it’s quite apparent that 17th century medicine had made little progress in the description of these complex and tragic neurological conditions. According to Willis,

The Apoplexy, according to the import of the Word, denotes a striking, and by reason of the stupendous Nature of the affect, as tho it contain’d somewhat Divine, it is called a sideration: for those that are seized with it, as tho they were Planet-struck, or smitten by an invisible Deity, fall on the Ground on a sudden, and being deprived of Sense and Motion, and the whole animal function (unless that they breath) ceasing, they lye dead as it were for some time, and sometimes dye out-right: and if they revive again, they are oftentimes affected with a general Palsie or an Hemiplegia. (quoted in Storey, C.E., 2007)

For the most part all these doctors could do is either watch the patient die or rely on the spontaneous healing powers intrinsic to the brain itself. During the Middle Ages brain damage was by necessity diagnosed on the basis of easily observable features and thus the typical neurological examination was rudimentary in nature, consisting largely on the basis of: “inspection, palpation of the pulse, and urinoscopy” (Walker, 1998, p. 157).

Until the 19th and 20th centuries, only sparse and intermittent advancement was made in the diagnostic categorization of disorders of consciousness owing to neurological damage. To give some representative examples of the slow terminological evolution, in the 17th century Thomas Willis used the term “coma” in his 1672 work De anima brutorum. In 1679 in Geneva Switzerland Theophile Bonet published Sepulchretum sive Anatomia Practica, a huge compendium of autopsy reports, 70 of which were cases of apoplexy. In the 18th century the Dutch botanist and physician Herman Boerhaave’s described the term “coma” in his lectures as follows:

It is the perfect image of a very profound sleep, like in healthy persons, due to exercise or fuddle. Therefore, there is little distinction, unless by duration. (quoted in Koehler, 2008)

Also of note, in 1898 Oppenheim distinguished between dazedness, somnolence, sopor and coma, which was one of the first modern taxonomies that systematically distinguished between different “levels” of consciousness.As we can see then, between the Middle Ages and the 20th century there was not a great deal of progress made in either diagnosing or treating apoplexy and the state of the field remained largely stagnant.

3.0 Contemporary Approaches to the Vegetative State

The modern history of the vegetative state begins with advances in EMT rescue and technology for sustaining bodily viability in the absence of normal brain function. The artificial respirator was invented in the 1950s by Bjorn Ibsen, a Dutch anesthesiologist who founded the first Intensive Care Unit. Since then, medical advances in artificial nutrition and hydration (ANH) enabled vegetative patients to live decades after the onset of brain damage without higher brain brain or evidence of awareness. The longest known case of VS is Elaine Esposito who was in a VS state for thirty-seven years. Surveys show that people perceive that living decades in this condition or ones similar to it would be a fate “worse than death” (Jennett, 1976) and most people including doctors would prefer to not be kept alive. Most patients deemed not to have a life worth living have ANH withdrawn, which is thought to release endogenous opioids and eventually lead to confusion and then coma from metabolic dysfunction.

Bryan Jennett, a British neurosurgeon and Fred Plum, an American neurologist, coined the term “persistent vegetative state” in a landmark paper published in Lancet in 1972 on April Fools Day. The paper was subtitled “A syndrome in search of a name”. The subtitle “in search of a name” is a reference to the fact that many similar descriptions of vegetative state were available at the time but none of them were broad enough to capture the vegetative state as a syndrome. For example, “Neocortical necrosis” is a term that was applied to a subset of vegetative patients but all such terminology was eventually replaced by terms that didn’t imply any particular causal etiology because of the heterogeneous causes that lead to behavioral unresponsiveness.

Extant medical vocabulary circling around at the time include the French term “coma vigil” Cairns’ term “akinetic mutism” in 1941 to describe a patient with “silent immobility”, German psychiatrist Kretschmer’s term “apallic syndrome”, Stritch (1956) discussions of “severe traumatic dementia”, Arnaud’s term “pie vegetative” in 1963, and Finnish neurosurgeon Vapalahti and Troupp’s “vegetative survival” in 1971. Most of these terms were never universally adopted for the same reason: they were over-specific with respect to the neurological damage or behavioral sequelae. Hence, because Jennett and Plum’s original vegetative syndrome was operationally defined only by a lack of behavioral responsiveness rather than any specific neurological deficit, the term started to enter the general medical lexicon and eventually made it’s way (controversially) into the public sphere due to many high-profile legal cases. Accordingly, Jennett and Plum were not the first to use the phrase “vegetative” nor were they the first to notice and describe the syndrome, but the name they chose stuck and has been in use ever since (though there is now efforts to rename the syndrome; see below). Fred Plum went on to write an influential textbook in the field with Jerome Posner called Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma, which is still in use and currently in its 4th edition (Posner et al., 2008)

The usage of the word “vegetative” to describe people with severe brain damage has always been controversial amongst the general public. One possible reaction to the term is to see it as violating the dignity of the patients by comparing their mental life to that of vegetables. But in the defense of Jennett and Plum, when they first coined “vegetative state”, they referenced the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of the verb “vegetate”, meaning “To live a merely physical life devoid of intellectual activity or social intercourse”. This usage of the term “vegetate” can be traced back to Ancient Greece e.g. Aristotle’s talked about a “vegetative soul” that was present in all living things including humans. In this respect the term “vegetative” was always meant to be a purely descriptive term for the mental capacity of the patients but it’s hard for laypersons not to read into the term some kind of pejorative connotation.

3.1 Assessment Scales

The history of diagnosing VS and related disorders of consciousness goes hand in hand with the development of behavioral assessment scales and recovery scales. One of the original assessment scales–still in use today–is the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) developed by Jennett and Teasdale (1974). The GCS involves 3 dimensions (eyes, verbal, and motor). The eye dimension is graded on a 4-point scale, verbal on a 5 point scale, and motor on a 6 point scale. Thus, the highest possible score is 15 indicating normal consciousness and 3 the lowest, indicating coma or brain death. On the recovery side of things, the Glasgow Outcome Scale was proposed by Jennett and Bond (1975) and describes 5 levels of brain function ranging from coma to VS to severe, moderate, and low cognitive disability. In terms of diagnosis, the JFK Coma Recovery Scale-Revised is currently the gold standard and best validated assessment protocol for diagnosing vegetative patients (Giacino et al., 2004). It involves 6 subscales including auditory, motor, verbal, and visual components. The test is designed to use only observable responses to bedside commands and tests, which allows the test to be used cheaply so long as performed in the hands of trained experts.

3.2 Minimally Conscious State

Today the diagnosis of vegetative state has become more complex and multifaceted in order to recognize the greater heterogeneity and range of cognitive abilities of people diagnosed with the blanket term “vegetative”. Recognizing the need for a more nuanced diagnosis to distinguish patients who are largely vegetative but show intermittent and non-repeatable signs of consciousness, the term “minimally responsible state” (MRS) was introduced by the American Congress of Rehabilitation in 1995. The difference between this and coma or PVS was that MRS required the observation of something “unequivocally meaningful” to the examiner. Later, a group known as the Aspen Workgroup recommended MRS be replaced by “minimally conscious state” (MCS) to emphasize that behavioral responsiveness can occur without consciousness. An estimated 100,000 to 280,000 cases of MCS are thought to exist in the US. The current consensus is that Giacino’s (2002) diagnostic criteria is the gold standard for assessing MCS. Giacino’s definition involves 4 levels of “non-reflexive” behavior:

- Following simple commands,

- Gestural or verbal yes/no responses (regardless of accuracy,

- Purposeful behavior such as those that are contingent due to appropriate environmental stimuli and are not reflexive.

- Intelligible verbalization.

Any demonstration of these abilities warrants the diagnosis of MCS instead of VS. Currently, these assessment scales like an overarching theoretical basis and without an accepted theory of consciousness it’s unclear whether consciousness is necessary for command following or purposeful behavior, especially given the many apparent counter-examples in clinical neuroscience such as blindsight (c.f. Levy, 2009).

3.3 Famous cases

The modern history of the vegetative state cannot be told without reference to the famous legal cases that were crucial in spurning interest and research on the condition from neurologists, ethicists, and the public at large. These cases operated as catalysts for more precise diagnostic criteria as well as standardization of assessment scales that can be implemented objectively by independent hospitals.

Karen Quinley

Karen Quinley’s case is famous for its association with the right-to-die movement. Karen Quinley was 21 in 1975 when she was found unconscious after an overdose of drugs and alcohol with her friends. After 5 months on a respirator Karen was still in a vegetative state and being cared for in the intensive unit. Karen’s parents, the Quinlans, requested that her respirator be removed because it was deemed by the Catholic church an “extraordinary” medical intervention and thus its removal would not constitute euthanasia, a procedure prohibited by the Catholic doctrine. However, Karen’s neurologist objected to removing the respirator, arguing this would be tantamount to killing her. Eventually the case went to the Supreme Court of New Jersey and the judges decided that the duty to protect life was overridden by the dim prognosis of future awareness. After Karen’s respirator was removed she was still on artificial nutrition and remained alive for another ten years.

Terri Schiavo

On February 25, 1990 Teresa “Terri” Schiavo (age 26) suffered a heart attack and lapsed into a coma. After two months with no signs of recovery, Schiavo was diagnosed with vegetative state disorder (VS). After several years and no signs of recovery, her husband asked to remove her feeding tube. Schiavo’s family objected, arguing that she showed intermittent signs of awareness. Subsequent legal battles involved 14 appeals and widespread media coverage but fifteen years after Schiavo’s heart attack a judge finally ordered her feeding tube to be removed and she died three days later on March 31, 2005.

When Schiavo was diagnosed, VS had not yet been widely distinguished from what is now called the minimally conscious state (MCS), a once controversial diagnosis. MCS patients are similar to VS patients but intermittently show clear signs of consciousness such as purposive behavior but these signs often cannot be reproduced. Once MCS became an established diagnosis (Giacino, 2004), Schiavo’s family later argued in court that she was in a MCS not VS and several doctors testified to this effect. Nevertheless, the judge ruled that Schiavo was in a VS state and that her condition was irreversible.

4.0 21st Century Approaches to the Vegetative State

Investigation into VS and related disorders has exploded in the 21st century. One of the biggest developments in the field came when Adrian Owen and his team published a paper in 2006 in Science claiming to have detected residual levels of consciousness in a patient clinically diagnosed with VS. This discovery sparked intense debate about the methodology and philosophical assumptions of the study but skeptics were finally answered in 2010 when Monti (2010) did a follow-up replication with 50+ subjects. In Monti’s study they found 3 patients in the vegetative state who were capable of “willful modulation” using Owen’s mental imagery paradigm. More recently, a 2014 study published in The Lancet found at least 13 cases of residual cognitive function in patients otherwise diagnosed with vegetative state disorder

4.1 Unresponsive wakefulness syndrome

Unresponsive Wakefulness Syndrome (UWS) is a new term for VS (Laureys et al., 2010; Laureys & Boly, 2012) that is more respectful of patient dignity as well as more diagnostically accurate. Although the term “vegetative” is accurate as a medical generalization across a population of patients, the problem comes when clinicians diagnose a particular person.It’s one thing to talk about vegetative patients in the abstract but if a doctor described your loved one as “vegetative” it would be hard not to find this an frightening, alien label. Despite its pretension to be a merely descriptive term, “vegetative” has negative connotations of a life not worth living, of being “vegged out”.

Furthermore, because modern neuroimaging techniques can now detect residual cognitive function that escapes bedside assessment, it is hasty to infer a patient lacks all cognitive function until they have been systematically tested using the latest technology. The term “vegetative” is inaccurate as a blanket diagnostic label because it ignores the possibility that they will find residual cognitive function using neuroimaging and other techniques that go beyond bedside behavior. The term “unresponsive” is therefore more appropriate than “unaware” and encourages clinicians to not use a single, monolithic state to describe what is in reality a complex continuum. Even though VS is a purely behavioral diagnosis and by itself strictly entails nothing about the presence or absence of consciousness, it’s hard even for clinicians to not adopt a “clinical nihilism” towards these patients despite the very real possibility of these patients having residual cognitive function that – if expressed – would change the diagnosis. However, it’s crucial to realize that there is no logical or empirical basis for inferring the absence of awareness from the absence of a behavioral response, especially since we know through retrospective report that locked-in patients who emerged from total lock-in syndrome were often thirsty, in pain, and aware of nurses and doctors talking around them but completely unable to move any muscles. We also know from retrospective reports of patients under general anesthesia that approximately 1-2 per 1000 cases report some degree of awareness during anesthesia even though they showed no overt motor response detected by the surgeons (Sebel, 2004).

There are many reasons why someone’s awareness would not be detected by a clinical test even if was actually present (Sanders et al., 2012). If we want to hold onto the idea that consciousness as subjective experience is something we share with animals, it’s not obvious why an ability to report one’s experience is necessary to having an experience in the first place. Hence, despite the careful qualifications of the original inventors of the label “vegetative state”, the term has taken on a life of its own and now probably does more harm than good by priming people to think about consciousness as being either “on” or “off” when reality is more complicated, with VS patients as a population being heterogeneous and falling along a broad spectrum of states – not one monolithic neurological or experiential state (Laureys & Boly, 2008).

4.2 Future Developments

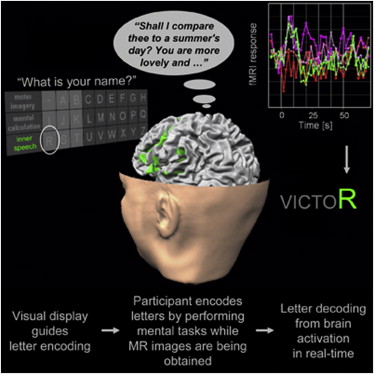

The future of coma science will likely involve the further implementation of advanced neuroimaging technology into the standard practice of clinical diagnosis. Already research teams across the globe are racing to build the first truly validated “consciousness-o-meter” that can be used to quickly diagnosis an unresponsive patient’s level of consciousness without relying on traditional behavioral assessment scales which rely on the subjective judgment of expert raters (Casali et al., 2013). The future will also involve the development of better brain-computer interface techniques to interact with UWS patients who emerge into locked-in syndrome, such as Sorger et al.’s (2013) real-time fMRI speller method (Fig. 2). The future will also bring new developments in therapeutic intervention to help foster neural plasticity and functional recovery using stimulation techniques like transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) or deep brain stimulation (Schiff et al., 2007) in addition to pharmacological interventions using anti- insomnia drugs like zoldipem (Brefel-Courbon et al., 2007).

Fig. 2 From (Sorger et al., 2013).

Conclusion

The concept of vegetative state has been loosely recognized, categorized, and discussed for thousands of years but it has only really been in the last 40 years or so that the condition has been rigorously defined and studied using the modern methods of clinical science. Ironically, the more rigorously VS is studied the fuzzier its definitional boundaries become, with most researchers now conceiving of the VS “state” as just one specific band in a continuous, multidimensional spectrum of cognition function. Thus, the more we study the vegetative state the more we realize that the term itself should be abandoned and replaced with a clinically validated set of consistent terminology based on an conceptually and empirically coherent understanding of consciousness that acknowledges a spectrum of possible states a patient could be in when they are seemingly unresponsive to the proddings an external observer.

References

Brefel‐Courbon, C., Payoux, P., Ory, F., Sommet, A., Slaoui, T., Raboyeau, G., … & Cardebat, D. (2007). Clinical and imaging evidence of zolpidem effect in hypoxic encephalopathy. Annals of neurology, 62(1), 102-105.

Casali, A. G., Gosseries, O., Rosanova, M., Boly, M., Sarasso, S., Casali, K. R., … & Massimini, M. (2013). A theoretically based index of consciousness independent of sensory processing and behavior. Science translational medicine, 5(198), 198ra105-198ra105.

Clarke, E. (1963). Apoplexy in the Hippocratic writings. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 37, 301.

Giacino, J. T., Ashwal, S., Childs, N., Cranford, R., Jennett, B., Katz, D. I., … & Zasler, N. D. (2002). The minimally conscious state definition and diagnostic criteria. Neurology, 58(3), 349-353.

Giacino, J. T., Kalmar, K., & Whyte, J. (2004). The JFK Coma Recovery Scale-Revised: measurement characteristics and diagnostic utility. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 85(12), 2020-2029.

Gosseries, O., Bruno, M. A., Chatelle, C., Vanhaudenhuyse, A., Schnakers, C., Soddu, A., & Laureys, S. (2011). Disorders of consciousness: what’s in a name?. NeuroRehabilitation, 28(1), 3-14.

Jennett, B. (1976). Resource allocation for the severely brain damaged.Archives of neurology, 33(9), 595-597.

Jennett, B., & Plum, F. (1972). Persistent vegetative state after brain damage: a syndrome in search of a name. The Lancet, 299(7753), 734-737.

Jennett, B., & Bond, M. (1975). Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage: a practical scale. The Lancet, 305(7905), 480-484.

Karenberg, A. (1994). Reconstructing a doctrine: Galen on apoplexy. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, 3(2), 85-101.

Koehler, P. J., & Wijdicks, E. F. (2008). Historical study of coma: looking back through medical and neurological texts. Brain, 131(3), 877-889.

Laureys, S., & Boly, M. (2008). The changing spectrum of coma. Nature Clinical Practice Neurology, 4(10), 544-546

Laureys, S., Celesia, G. G., Cohadon, F., Lavrijsen, J., León-Carrión, J., Sannita, W. G., … & Dolce, G. (2010). Unresponsive wakefulness syndrome: a new name for the vegetative state or apallic syndrome. BMC medicine, 8(1), 68.

Levy, N., & Savulescu, J. (2009). Moral significance of phenomenal consciousness. Progress in brain research, 177, 361-370.

Monti, M. M., Vanhaudenhuyse, A., Coleman, M. R., Boly, M., Pickard, J. D., Tshibanda, L., … & Laureys, S. (2010). Willful modulation of brain activity in disorders of consciousness. New England Journal of Medicine, 362(7), 579-589.

Owen, A. M., Coleman, M. R., Boly, M., Davis, M. H., Laureys, S., & Pickard, J. D. (2006). Detecting awareness in the vegetative state. Science, 313(5792), 1402-1402.

Posner, J., Plum, F., Saper, C., Schiff, N., &.(2007). Plum and Posner’s Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Sanders, R. D., Tononi, G., Laureys, S., & Sleigh, J. (2012). Unresponsiveness≠ unconsciousness. Anesthesiology, 116(4), 946.

Schiff, N. D., Giacino, J. T., Kalmar, K., Victor, J. D., Baker, K., Gerber, M., … & Rezai, A. R. (2007). Behavioural improvements with thalamic stimulation after severe traumatic brain injury. Nature, 448(7153), 600-603.

Sebel, P. S., Bowdle, T. A., Ghoneim, M. M., Rampil, I. J., Padilla, R. E., Gan, T. J., & Domino, K. B. (2004). The incidence of awareness during anesthesia: a multicenter United States study. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 99(3), 833-839.

Sorger, B., Reithler, J., Dahmen, B., & Goebel, R. (2012). A real-time fMRI-based spelling device immediately enabling robust motor-independent communication. Current Biology, 22(14), 1333-1338.

Stender, J., Gosseries, O., Bruno, M. A., Charland-Verville, V., Vanhaudenhuyse, A., Demertzi, A., … & Laureys, S. (2014). Diagnostic precision of PET imaging and functional MRI in disorders of consciousness: a clinical validation study. The Lancet.

Storey, C. E. (2007). Apoplexy: Changing Concepts in the Eighteenth Century. In Brain, Mind and Medicine: Essays in Eighteenth-Century Neuroscience (pp. 233-243). Springer US.

Teasdale, G., & Jennett, B. (1974). Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: a practical scale. The Lancet, 304(7872), 81-84.

Walker, A. E. (1998). The Genesis of Neuroscience. The American Association of Neurological Surgeons